ISABEL DOMINGOS E JOÃO APPLETON, ARCHITECTS

Between the elegance of faktura and the energy of the event

The exhibition is a fundamental device of 20th-century art.

We may even phrase this a little more assertively: the 20th century has created a new device for art, which is the exhibition, with all its procedures, protocols, practices and spaces.

The emergence of the exhibition as a device could not fail to influence artistic creation. Artists, indeed, started producing pieces for specific exhibitive situations, in two different ways: as interventions in a definite space that becomes the subject of the intervention itself, or as a reflection on the exhibitive issue as the main narrative of the artistic in art.

This change is chronologically close to another: the appearance of the modern and contemporary art museum as an institution that redefines, organises, disciplines and generates discourse on the exhibitive language from a structure of thought that stems, first, from Art History, then from the construction of a phenomenology of spatial experience and finally as a condition that does away with the spectator/work, subjectum/objectum relationship, to try and define a different one, which relinquishes the “in front of” category and uses this new approach to reject the traditional relationship of the aesthetics of taste, disinterest and detachment, one of the fundamental aporias of modernity. This development proposes a logic of hypermodernity rather than a rupture with historical modernity, in spite of the fact that the latter is strongly influenced (in terms of both theoretical discourse and artistic jargon) by an interpretative legacy focused on formalism and grand historical narrativity, both of which are clearly insufficient to encompass the complex range of the modern phenomenon, even in terms of its meta-discursive version (Modernism) or its Mannerist incarnation (the Avant-garde).

The museum, like the exhibition gallery, was introduced by the new political regime that emerged from the French Revolution, but the museum of modern and contemporary art is a German (and later American) invention from the second half of the 20th century. The museum as an institution that displays contemporary work has its most successful incarnations in the Hanover Landesmuseum, directed by Alexander Dorner, and later in the MoMA under the direction of Alfred H. Barr, ably assisted by Phillip Johnson. It was probably during Barr and Johnson’s trip to Germany and Russia, in 1926, that the museological, curatorial, scientific and architectural typology that brings about the clearing of the exhibitive space, the construction of a spatial narrativity and the concept of installation that shape the modern art museum was first defined.

The MoMA’s exhibitive structure reflects Barr and Johnson’s thoughts on the depuration of the exhibitive space, the wall’s necessary neutrality and the didactic and comparative logic of the exhibitive process which form the corollary of the “rocket-shaped” historic diagrams, influenced by a genealogical approach, which Barr defined in accordance with Johnson’s thought, which was clearly oriented by principles of genetic depuration (indeed, Johnson would become a fervent Nazi sympathiser over the next two decades, though his aesthetic open-mindedness was clearly at odds with the rurality of German National Socialism).

One of the most important experiments Barr and Johnson witnessed in Germany was Alexander Dorner’s refurbishment of the Landesmuseum, which would have its corollary when he invited Lazar Lissitzky (first) and Moholy-Nagy (later) to design two cabinets, one for abstract art and the other for kinetic art.

The Kabinet für Abstrakte Kunst, conceived by Lissitzky and open to the public in 1927, was a space in which perception depended on the movement of the visitor. It was one of the first experiments in constructing a space of artistic enjoyment dedicated to reversing the contemplative relationship.

Indeed, Lissitzky was invited because of his Proun space, in which he had been working since 1919 (the first Proun drawing is currently in Portugal, at the Berardo Collection). It was shown to the public in 1923, during the Grosse Berliner Kunstaustellung, and a reconstruction of it can be seen at Eindhoven’s Vanabbe Museum (the director of this Dutch museum made the reconstruction by from a 1923 lithograph, Kestnermappe nº 6).

Both the Proun space – which consists of a three-dimensional rendering of issues first raised by Malevich in 1915 – and the Kabinet are instances of the conversion of the exhibition into an art form, or even of turning the exhibitive space itself into a work of art.

This means that the space in which the exhibition is held stopped being, after Lissitzky (to whom we might add a lineage in 20th-century art that includes Kurt Schwitters, Edward Kienholz, Allan Kaprow, Robert Rauschenberg, Yves Klein, Lucio Fontana, Robert Morris and Barry Le Va, right up to Gregor Schneider), an element in artistic creation to become the transcendental of art.

In other words, the condition of possibility of the work of art’s presence became a phenomenological determination of the exhibitive space, besides being a condition of the ontological viability of the work of art’s public situation. We might also add, in a more radical formulation: in hypermodernity, the exhibitive space has taken the place of the frame, or of the work’s outer edge, allowing for its extension up to the limits of the exhibitive condition, which, we are aware, can extend itself into the broad (widened) field of the territory – as a three-dimensional version of cinema, rather than a further dimension of architecture.

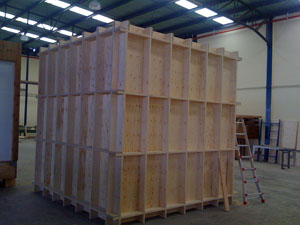

Thus, the decision of returning to a delimited space within the exhibitive space corresponds to a possibility of archaeologically restoring a circumscribed exhibitive condition, as an essay – in the Kirkegaardian sense –, a repetition of a situation that denotes a standard procedure. This particular condition of the Empty Cube project is part of an attempt at rethinking the performative quality of a space, whose existence deeply relies on an ephemerality that heightens its quality of event.

These two conditions – the cabinet d’amateur-like construction of a space within a space (with all the Perec references it inspires), which causes the project to be separated from contact with the gallery, and the situation’s ephemerality – turn the exhibitive problem into a performative issue.

In other words: the development of a structure that was thought, conceived and developed so that it could be installed and removed in a (very) short time frame implies an emphasis on the performative quality of the exhibitive space itself, since it is its very performance as an element that transcends the artistic process that comes under scrutiny here. On the other hand, it becomes a machine for generating relations and sharing, in terms of its condition as an event.

It is in this sense that its condition as a micro-event invokes a set of social and collective protocols concerning the fleeting disclosure of the development of a physical space, of its potential as a field of intervention possibilities, but also of re-equating the place under the sign of “as if” (as if the space were real, as if it were permanent, as if it were a re-edition of its historical models, etc.).

That is why the Empty Cube project is one of the most ambitious, clear, synthetic and focused artistic projects in my knowledge: because the temporary fiction of a community of sharing it defines combines the constructive elegance of its exact faktura with the event’s performative ability.

Delfim Sardo